On Time

August 22, 2020

Happy August! If you are like me, your kids are slowly starting back to (some sort of) school, and things are a little hectic at home. My two daughters are actually going for in-person learning, but every parent we know is laying bets on when they’ll all get relegated back to Zoom U. Alas Labor Day is the current Vegas over/under…

Let’s pick back up where we left off last month, discussing the first step towards fungible retail. Like much in life, the first step is to admit we have a problem, only this time with “credit.” Our addiction to it is partially to blame for the retail mess we’ve all gotten ourselves into, but it isn’t the only culprit. Our concepts of space and time are also part of the problem, and in this note I want to deal with time.

Did you ever see the Arthur C. Clarke documentary on fractals? It came on late at night in the ‘90s. If you got home at 3am from a night of drinking, you’d turn it on and blow your mind before you passed out on the couch (not me; this happened to a guy I knew).

A fractal is a mathematical model for something that is infinitely complex, meaning that a large pattern is really made up of smaller groups of identical patterns, which in turn are made up of smaller groups of identical patterns, and so on and so forth. One mathematical textbook notes that fractals can be used to describe “seemingly random or chaotic phenomena such as fluid turbulence or galaxy formation.”

And, it turns out, real estate finance.

Real estate capital stack org chart

All of modern finance is a fractal in a way, because small repeating components make up the larger whole. The mortgage lender leverages a little bit of their equity against deposits. The debt fund uses that bank loan to juice their equity returns. The limited partner uses that debt fund to juice theirs, and the general partner uses the LP equity to juice whatever last bit of equity they’re required to contribute.

On top of all that comes the tenant. Historically landlords have insisted that retail tenants pay for as much of the total build-out cost as possible. Preferably all of it. In theory the tenant gets to leverage all of the money spent before it. Their cash is just another fractal.

From the landlord’s perspective, this tenant investment in the space is Skin In The Game. Skin, the conventional wisdom goes, makes the retailer work harder. Put aside for one minute that there is no data that shows any correlation between tenants’ buildout costs and success. In reality, requiring substantial Skin In The Game has a number of dismal knock-on effects for landlords, the most egregious of which are profits and time.

Let’s start with a hypothetical real estate project. Imagine that you bought one square foot of retail for $400 and invested another $100 for tenant improvements. $100 isn’t enough to build this out this particular square foot, so the tenant will take that $100 and put in perhaps another $100 of their own.

Or to be more accurate, the (smart) tenant will get $50 from investors and borrow $45 from the SBA and then they’ll put that last $5 in to cover what’s left. Fractals!

In this hypothetical case the tenant might pay the landlord $32 a year in rent but if all goes well hopes to make $50 a year in profit. Their $100 represents only 16% of our hypothetical capital stack yet it gets 60% of the (before rent) EBITDA!

This is a terrible misalignment of risk and return for the landlord, but just as importantly that relatively small investment will entitle the tenant to use that space for a really, really long time. In exchange for investing $100 the tenant will ask for years and years of lease term with options galore thereafter. They need that time, because unlike the building the business doesn’t really have an exit value. The more money the operator spends on the space, the more time they need to get their investment back.

Maybe it all goes well for everyone. It often does. But then maybe along the way the tenant will have made their money and will be focused on something else. But the landlord isn’t in control. Or the concept will get tired and will need a refresh, but what tenant wants to invest new money into an old Tiki Bar when Tiki Bars are so 2016?

So what if you played this hypothetical investment another way? Let’s say you and your investors put all of the money in ($600 now) and you build out that square foot exactly like you want it. Your tenant isn’t really a tenant: they’re a manager or a partner and while they’re incentivized by a promoted percentage of the profits, you the landlord are going to take the bulk of it home.

Now your $500 isn’t making $32 a year: your $600 is making $60 if it all goes well. And maybe more importantly, if it doesn’t go well you tweak the concept or find another operator. You’ve designed the space for the vision you’re trying to create, so it’s a matter of finding the right group to execute it. Or a better question: what if the potential rent on that retail space is just a drop in the bucket? What if that square foot’s highest calling is as an amenity to all of the office and apartments square feet you also own upstairs? Then exchanging landlord control for tenant money seems even more short-sighted.

We had envisioned this amazing Bloodthirsty Hungarian Gangster-themed fondue restaurant, but couldn’t find the right group to run it.

This isn’t a new concept. Jamestown and a few other groups have been doing it for years. Applying this approach to restaurants and music venues and event spaces is just the logical extension of pop-up retail, which caused quite a stir just a few years ago but is now a la mode. In the next few years I suspect there will be a lot of potential operators without a lot of potential capital, so fractal capital stacks may be forced to adjust.

This is about creating hospitable retail. Having more control / shorter leases on space is the second step towards fungibility. I’m not saying that tenant investment in the space is always bad. Sometimes it’s a sign that they have investors who believe in the concept. But tenant investment is bad when it so radically skews the economics, and it’s really bad when the tenant invests so much that it forces the landlord to cede control.

There is more to fungibility, and we’ll continue talking about it next month. This answer isn’t for everyone or even every place. But over the next few years fungibility will increasingly be the best answer for most experience-driven projects.

Where We’ve Been. We’re traveling again, and so far I gotta tell you: the flying is fantastic when there’s almost no one in the airport but you. It reminds me of a favorite old Onion headline: “98% of US Commuters Favor Public Transportation for Others.”

Delta Airlines is handling it all with aplomb. Middle seats are open. Everyone has masks and it’s all impeccably clean. We were in Cincinnati two weeks ago, South Carolina last week, and are headed to Denver next week and then Dallas after that.

Article after article (mostly written by Boomers) has compared 2020 to all sorts of years in the late 60s, so here are some suggestions to get you into the spirit of those tumultuous times, starting with the The Game: Harvard, Yale and America in 1968. Al Gore, George W. Bush, Tommy Lee Jones and Meryl Streep all make an appearance in this great book about the 1968 college football game called by many the best ever.

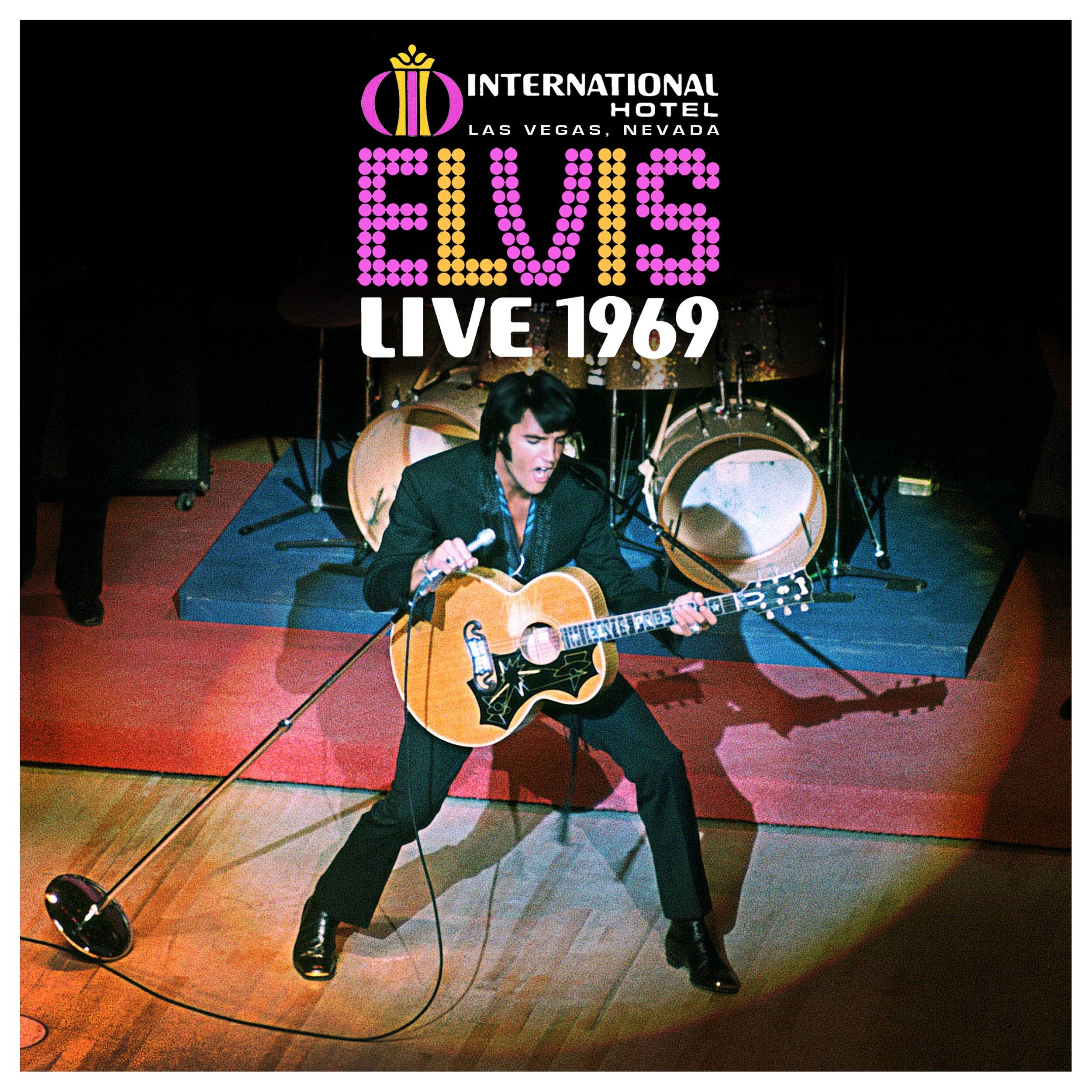

In the summer of 1969, while America was focused on the moon and Vietnam and Woodstock, Elvis returned to the stage after a decade making movies. Backed by his favorite musicians and a 40-piece orchestra, even Rolling Stone magazine called his seven-week gig “supernatural.” The delightful book Elvis In Vegas shows not just how Vegas saved Elvis, but arguably how Elvis saved the city.

On April 13, 1970 the crew of Apollo 13 famously radioed “Houston, we’ve had a problem.” You’ve no doubt seen the movie, but season two of the BBCs 13 Minutes To The Moon podcast is superb, interviewing dozens of participants over eight episodes. This is heart-pounding stuff: each problem solved uncovers a dozen new ones. The battery they flew back on? It only had enough power to run a hair dryer for three hours.

1971 would become one of the most eventful years in the early days of rock. The Stones started their journey from band to brand, Led Zeppelin invented arena rock, and Paul McCartney sued to leave the Beatles. David Hepworth’s Never A Dull Moment: 1971 The Year Rock Exploded covers it all in enjoyable (albeit stereotypically “gushing rock reporter”) detail.

I’m a little late to the party, but if you haven’t dived in to Slate’s Slow Burn podcast you owe it a listen. Now onto season four and covering subjects from Tupac and Biggie to Bill Clinton, Season One is a fantastic deep dive into many of the lesser-known (and still sordid) details of 1972’s Watergate break-in and cover up. We’re still dealing with the consequences.

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading this. This note comes (mostly) monthly and if you’re interested in adding your name to the mailing list, just click here. All of our past notes can be found here.

We’d love to hear from you if you’re working on something unique or unusual, which to be honest pretty much sums up all retail these days. Stay strong! We’ll all get through this and before you know it there will be all sorts of opportunities (and fun) to be had.

Cheers,

G